Scientists reverse periodontitis in aged mice

In Brief:

- A drug targeting an aging-related molecule reversed periodontal disease in elderly mice.

- The results suggest periodontal disease and other age-related conditions share a common biology, and that targeting this pathway might improve oral health for older adults.

As we age, we’re at increased risk for conditions like diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and gum disease, or periodontitis. It’s estimated that more than 60% of adults ages 65 or older have periodontitis, which is marked by changes in oral bacteria, inflamed bleeding gums, painful chewing, and even loss of teeth and surrounding bone. While treatments may help keep periodontitis from getting worse, there’s no cure.

A recent study, however, raises the possibility that periodontitis can be reversed, at least in mice. The research was led by Jonathan An, DDS, PhD, as part of an NIDCR fellowship supporting his DDS/PhD training at the University of Washington in Seattle. The team showed that an FDA-approved drug targeting an aging-related pathway reduced periodontal disease in elderly mice. The findings point to a potentially powerful new target for enhancing the oral health of older adults.

During his dental training, An had noticed that periodontitis in his older patients often occurred along with other age-related disorders like diabetes. “As dentists, we know certain measures of overall and oral health decline with age, but we don’t know how to fix them,” says An. “I was interested in applying basic science to that problem in the oral cavity.”

He approached Matt Kaeberlein, PhD, director of the University of Washington’s Healthy Aging and Longevity Research Institute, and proposed that periodontitis may share the same aging-related biology thought to underlie conditions such as Alzheimer’s, heart disease, and diabetes.

One such aging-related molecular pathway involves a protein complex known as mTORC1 (mechanistic target of rapamycin complex I). Over the last two decades, Kaeberlein and others have shown that mTORC1 is linked to lifespan in yeast, worms, fruit flies, and mice. Blunting mTORC1 activity with an FDA-approved drug called rapamycin, which is primarily used to prevent organ transplant rejection, is known to extend lifespan in these organisms. Treating mice with rapamycin delays or reverses age-related decline in immunity and in brain, muscle, and heart function. In humans, early findings hint at the drug’s ability to improve immune function and reduce signs of skin aging.

For his dissertation work in Kaeberlein’s lab, An set out to explore whether periodontal disease is also influenced by the mTORC1 aging pathway. He showed that mice develop periodontitis as they age, with the same hallmarks of inflammation, microbial changes, and bone loss seen in humans.

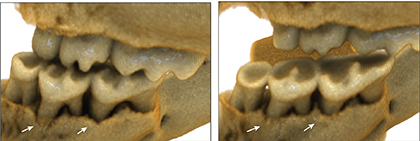

He and colleagues then treated 20-month-old mice (equivalent to 65 to 70 human years) with rapamycin for 8 weeks. Using a 3D imaging technique called micro-computed tomography, the group found that older mice in the treatment group regenerated lost bone. Genetic sequencing of the animals’ oral bacteria showed that rapamycin also seemed to return their microbial makeup to a state resembling that of younger, healthier mice. Markers of inflammation also declined to levels typical of younger animals.

“Rapamycin seems to set the clock partway back at both the molecular and functional level, slowing the aging process and thereby reversing aspects of disease, including bone loss,” says Kaeberlein. “If the drug works the same way in people, it could have a big impact, since a major proportion of older adults have periodontal disease.”

Now an acting assistant professor in the oral health sciences department at the University of Washington, An is currently working to set up his own lab. He plans to explore whether other pathways known to affect lifespan also affect periodontal disease and other oral processes affected by age, such as salivary gland function.

“Ultimately, I want to find ways to improve the aging process in the mouth so that older adults can maintain oral health longer,” says An.

Related Links

- Periodontal (Gum) Disease

- Older Americans Are Keeping More of Their Teeth

- Researchers Identify Immune Culprits Linked to Inflammation and Bone Loss in Gum Disease

Reference

Rapamycin Rejuvenates Oral Health in Aging Mice. An JY, Kerns KA, Ouellette A, Robinson L, Morris HD, Kaczorowski C, Park SI, Mekvanich T, Kang A, McLean JS, Cox TC, Kaeberlein M. Elife. 2020 Apr 28;9:e54318. doi: 10.7554/eLife.54318. PMID: 32342860.

Attention Editors

Reprint this article in your own publication or post to your website. NIDCR News articles are not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH's National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research as the source.

Subscribe to NIDCR Science News

Receive monthly email updates about NIDCR-supported research advances by subscribing to NIDCR Science News.