Cracks in the Code: What Really Keeps Teeth Strong

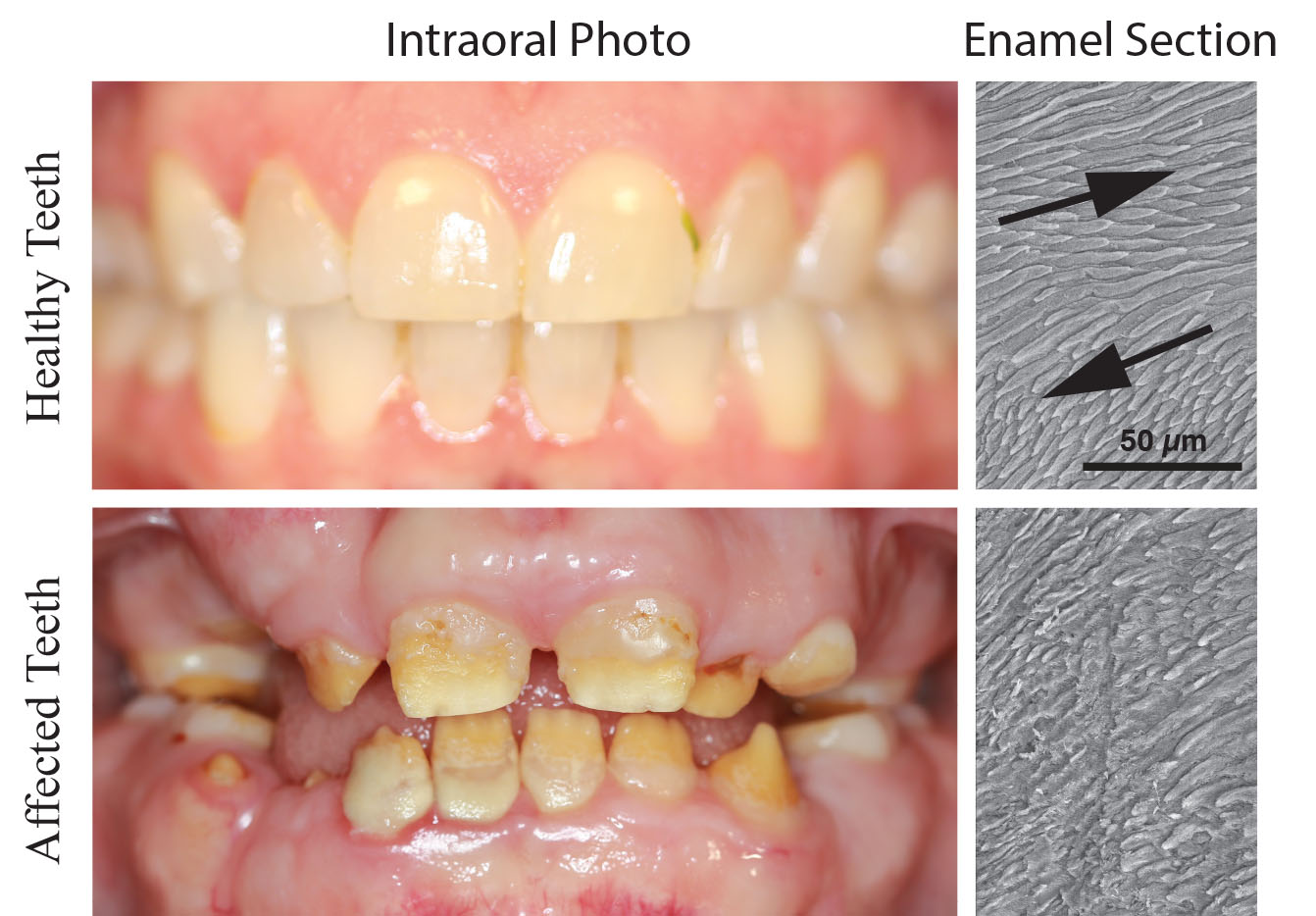

A disrupted internal structure can make teeth fragile

Enamel, the outer protective covering of our teeth, is the hardest material in the human body. Once damaged, enamel can’t heal itself like skin or bone can. So, cavities and cracks must be repaired by a dentist to keep our teeth healthy and functional.

Until now, scientists believed that strong enamel was a result of its thickness and mineral content. But a new study from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Intramural Research Program discovered that sometimes enamel can look totally normal in thickness and mineral content yet actually be weak and fragile.

Two of NIDCR’s intramural scientists, Dr. Janice Lee and Dr. Olivier Duverger, noticed this defect while studying patients with a rare disease called Loeys-Dietz syndrome type II that also affects the heart and other body structures. Based on radiographic images, these patients had enamel that appeared healthy before their teeth erupted during childhood. But after their teeth came in, the enamel chipped off easily. NIDCR researchers discovered that the culprit was disruption of the enamel’s internal structure.

Normally, enamel is built from tiny mineral rods arranged in a crisscross pattern, which gives it extra strength. In patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome type II, the special cells that make enamel (called ameloblasts) did not move in a precise, coordinated way resulting in the crisscross pattern failing to form correctly. As a result, the enamel breaks and wears down easily, even if it looks fine on an x-ray.

This finding could help explain why some people get cavities or cracks in their teeth, even if their enamel “looks” healthy. It shows the critical importance of enamel’s internal microscopic structure for normal function. These findings can help guide new tests, protective treatments, and therapies that strengthen and maintain smiles.

Reference

Duverger O, Wang SK, Liu QN, Wang Y, Martin D; NIDCD/NIDCR Genomics and Computational Biology Core; et al. Distinctive amelogenesis imperfecta in Loeys-Dietz syndrome type II. J Dent Res. 2025 Jul;104(8):840-850. doi: 10.1177/00220345251326094.

Attention Editors

Reprint this article in your own publication or post to your website. NIDCR News articles are not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH's National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research as the source.

December 2025