Why Studying Human Nerves Could Unlock Better Treatments for Chronic Pain

If you live with chronic pain, you’re not alone. About one in five adults in the U.S. experience pain that lasts longer than three months. For some, this pain is so disruptive that it interferes with everyday activities like working, cooking, walking, and even sleeping. Doctors often prescribe opioids to help, but these drugs can come with serious risks, including addiction, and they don’t treat the actual cause of the pain. In addition, much of what we know about pain comes from studies in rodents. However, promising drugs that have been found to ease pain in mice often fail in people. As a result, the search for safer, more effective treatments has been slow.

That may be starting to change.

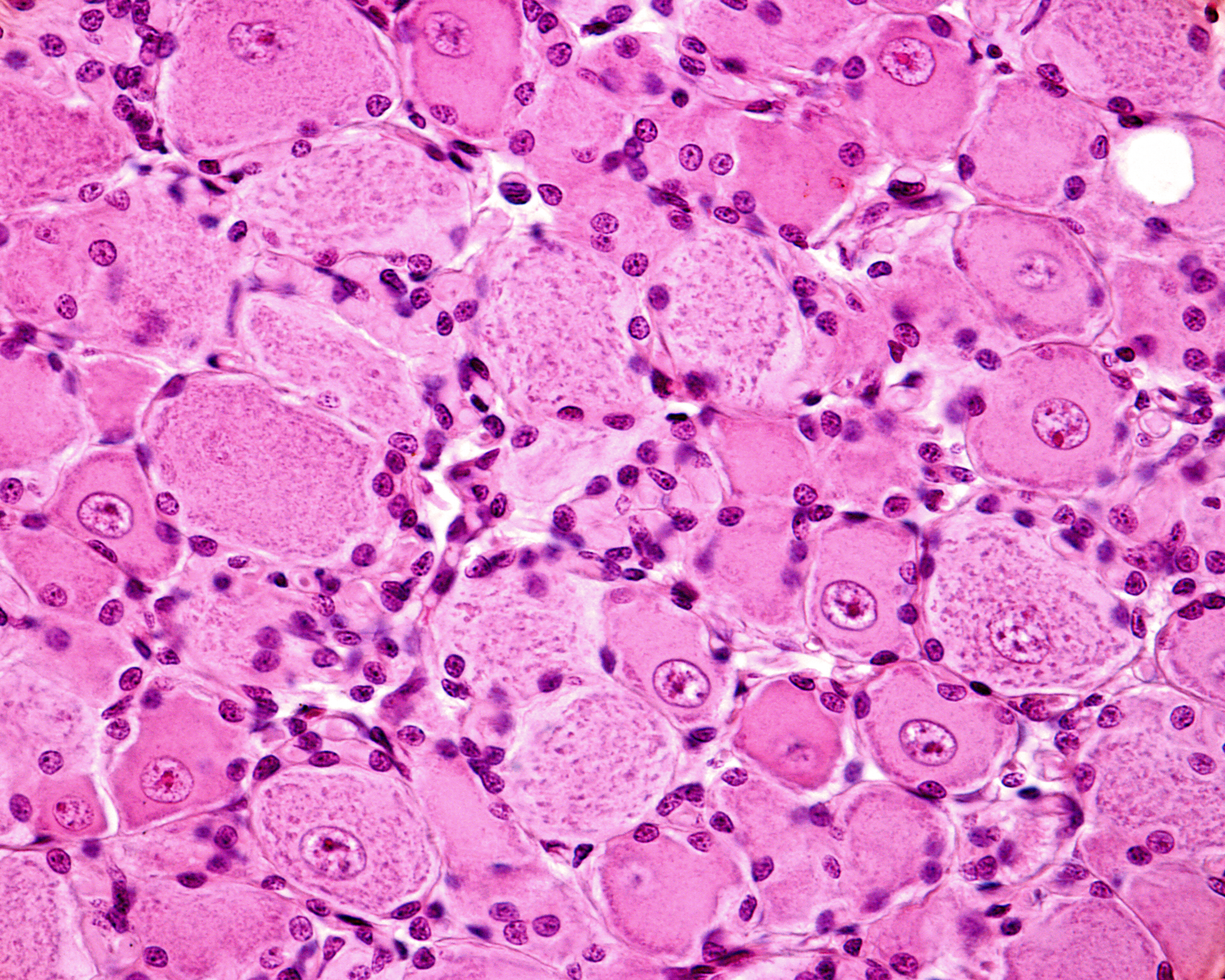

A recent review in Pain Reports details potential avenues to study the mechanisms that drive human chronic pain. Thanks to the availability of a new source of human nerve tissue, researchers now have an unprecedented opportunity to study the root causes of chronic pain. With permission from organ donors and their families, scientists can examine specialized nerve cells called dorsal root ganglia (DRGs). These are tiny clusters of nerve cells located outside the spinal cord. These clusters act like communication hubs, sending sensory information including pain signals. Researchers can study DRGs not only from healthy donors, but also from people who lived with chronic pain.

At the National Institutes of Health (NIH), scientists Ashok Kulkarni, Ph.D., and Bradford Hall from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) are using this resource to explore what goes wrong in the nervous system during chronic pain. The focus of their research is on two common but very different pain conditions: diabetic painful neuropathy (DPN) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In DPN, nerve damage is caused by high blood sugar, leading to burning or stabbing sensations in the limbs. In contrast, RA is an autoimmune disease where the body’s immune system attacks joints, causing painful inflammation.

By analyzing the activity of thousands of genes in DRG cells from donors with these conditions, the researchers spotted some striking patterns. In people with DPN, there was clear evidence of nerve cell loss, this damage is likely due to the effects of diabetes, driven by low grade chronic inflammation within the nerves. Interestingly, this kind of nerve death wasn’t seen in RA, instead genes tied to inflammation and nerve hyperactivity were increased.

That difference matters. It suggests that treatments for chronic pain may need to be personalized. A therapy that works for nerve-related pain might not help someone whose pain stems from other inflammatory processes.

In contrast, the researchers found that the two conditions also shared some common features. In both DPN and RA, signs of cellular stress and increased immune-related gene activity were seen. These similarities hint at shared biological pathways that could be targeted with new drugs, potentially helping people with multiple types of chronic pain.

The research is still in its early days, and the studies so far have involved only a handful of samples. But even this small step is a big leap forward. For the first time, scientists are studying chronic pain in human nerve cells, not just animal models.

The hope is that future studies, using larger numbers of donor tissues and more advanced methods, will uncover the precise mechanisms behind chronic pain and ultimately lead to safer, more effective treatments.

For the millions of people living with daily pain, this new window into the human nervous system could be the key to lasting relief.

Reference

Hall B, Cook L, Yun S, Kulkarni AB. Human pain transcriptomics: Lessons learned so far. Pain Rep. 2026 Jan 30;11(2):e1355. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000001355.

Attention Editors

Reprint this article in your own publication or post to your website. NIDCR News articles are not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH's National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research as the source.

Subscribe for NIDCR Updates

Receive email updates about the latest advances in dental, oral, and craniofacial research.

February 2026